How is green coffee graded?

What is a coffee quality score?

And, what grading criteria do we USE?

We’ll answer these 3 questions and more in the following discussion. For some coffee fans, this may feel like information overload. For other coffee pros, this may be a good primer to whet your appetite for the SCA Green Coffee Foundations course. More to come.

Coffee is “green” before it is roasted.

Coffee must be roasted before we can brew and enjoy it.

If you are a coffee roaster, then you have probably been solicited by green coffee sellers. They promise a beautiful crop and offer to send or drop off samples free of charge. They ensure you that this green coffee is off high quality at a great price.

However, it is very common that you may receive a 100g-300g sample which was cleaned by hand, to help you (the green buyer) to have a great first impression. This would in turn lead you to consider buying on the basis of a non-representative sample. After all you’ll be getting the real deal, from a 60kg bag.

As a roaster you may be convinced - this coffee is great! It’s clean and tastes great. “Give me 10 bags!” However, months later when the 10 bags roll in strapped to a +600kg pallet you may find that the coffee looks less clean. We’ll talk about “clean” and “defects” soon.

This may be a dramatic (I hope as a roaster you have had many positive experiences), but it does happen quite often that samples do not represent the actual product. So let’s consider what variables contribute to creating our Green Coffee Grading Scale. As a buyer, it’s essential we are on the same page as our seller.

When Grading Coffee on a Scale:

We grade by size

We grade by defect count

We grade by cupping scores

We grade by other criteria (elevation, etc.)

Together - we harmonize for common language

Size Matters, Or Does It?

Let’s talk about coffee size ratings and how they can easily lead our judgement astray. There are 2 major principles at work here when discussing size of coffee beans. One is much more important for final quality than the other. However, valuing (pricing) the coffee may not correlate in the end.

First, coffee beans should be sorted, shaken, sifted according to size. As a specialty coffee buyer, we seek a homogenous size when purchasing. A beans size should be as close as possible to it’s neighbor. Small beans are all together, medium beans are separated, and so on.

We measure size with coffee screens. Each size on a coffee screen is an incremental measure - the size of a hole in the screen. Those increments increase stepwise by 1/64 an inch. The most common screen sizes (diameters of holes) range from 10-20. Stated another way, super small beans fall through 10/64 inch (4mm) diameter holes while super large beans are suspended (not falling through) holes with a 20/64 inch (8mm) diameter. We would grade those small beans “screen size 10” while we grade the large beans “screen size 20+”. The graphic below offers some clarity and breakdown with conversions for various countries.

As you can see above (we are not to the 2nd point yet) there is some language introduced which could be misleading. Calling super large beans “AA” or “Supremo” sounds much better than a “B” or “Terceras”. Many taste tests have been done and we cannot conclude that large beans taste better (or worse) than small beans. More on that soon.

The second point, is about homogeneity. A coffee roaster wants their coffee to taste as good as it can, no matter where it comes from or how large the bean is. An essential part of roasting great coffee is consistency of roast development. Imagine roasting large items (beans) with very small items (beans). The large will roast at a different speed than the small and require different amounts of heat. When one is properly roasted another will not yet be ready. When the other is finally roasted properly, then former will be overdeveloped or burnt. This is an unfortunate and common phenomenon when large and small beans are all mixed together. There is also much more to be said about blending for espresso, but that will be left to another discussion entirely.

Defects Matter!

The best coffee is clean coffee. So how do we understand what is clean or “dirty”? Defects come from several key areas. One is pre-processing - something resulting from the farm and from nature. Another is during processing - something from mishandling or missteps in the process of removing seed from fruit. Another is during storage - before the coffee ever gets to a roastery (or heaven forbid in your roastery) while it’s sitting in the bag, on a truck or in storage.

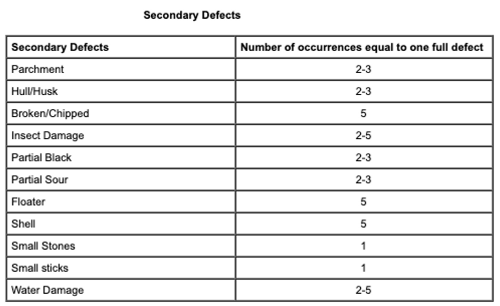

Defects are also broken down into 2 categories: Primary and Secondary Defects. Primary defects will knock your coffee out of “specialty” status with just 1 or a couple present. If your coffee has a few Secondary defects it may still qualify as “specialty” but you can’t have too many or it will again fall out of “specialty” status. It’s a simple chart to follow, but the challenge is personally delineating what defects constitute and to what severity each is. This is where working with a professional or getting some basic training in Green Coffee comes in helpful.

Insert plug with link for Green Coffee Foundations course : )

Cupping Scores (should) Matter!

It could surprise you that traditional coffee grade metrics are not based upon cupping scores. I can see a valid argument for and against this. We’ll look at both perspectives.

“Cupping” is a coffee term where we run quality control on a batch of coffee. It’s also super cool and super nerdy for many specialty coffee pros. Imagine a bunch of professionals dipping spoons into community bowls slurping and spitting with expressions of Mmmm… Ohhhh… while making notations on clipboards.

The notes we take in cupping constitute a score where 100 points are possible. No one ever scores a coffee a perfect 100. The most rare and beautiful coffees score in the 90s. Good coffees (and the majority of specialty) fall within the range of 82-88. However, when a coffee scores below 80 points, we must remove “specialty” classfication for it. Below 80 coffees are considered “commercial grade”.

Coffee Cupping Scores are comprised of:

Fragrance (quality and intensity)

Aroma (quality and intensity)

Acidity (quality and intensity)

Body (quality and intensity)

Flavor (quality)

Aftertaste (quality)

Balance (quality)

Sweetness (yes/no presence)

Uniformity (yes/no)

Clean cup (yes/no)

and an Overall rating (quality)

What does it mean, to not be clean?

If a coffee is not uniformly clean, then there is a “Taint” (minor infraction) or a “Fault” (major infraction). If a coffee has a Taint it is penalized -2 points for every cup with the taint. Many small human errors within the supply chain can introduce taints. The coffee may still be enjoyable and a common consumer may not notice the Taint. If discovered, the coffee may still be considered “specialty” with above 80 points, but the critical question becomes: “can we remove or resolve this taint?” Unless it’s a roaster error, there is little you can do to remove the taint. At that point, many tainted coffees will be dark roasted to cover up slight taint.

A “Fault” will be much more severe. Faults dominate your impression and the cup. They cannot just be roasted out or masked. These coffees will often be sold for commercial and instant coffee use or they may be flavored with chemicals and syrups to mask the extremely unpleasant character they have taken on.

A coffee with soft or subtle traits (following) may be called a “taint” while those with dominant and overbearing traits listed below would be classified as a fault. These include:

Fermented or Mouldy

Musty or Rioy

Earthy or Potato or Raw Peanut

Unripeness or Greenness

Hard or Astringent cup

Woody or Pulpy

Rubbery or Petroleum

And more.

Pulling it all together.

The coffee industry has the benefit (and at times encumbrance) of long tradition. Coffee growing nations and practices are disperse and disparate across the world. As a result various practices and standards have evolved. While we have learned from one another, we also have formed regional, national and cultural habits around coffee. One of those key factors includes coffee grading and quality measures as they have evolved through language and time.

Due to the wonderful diversity in coffee around the world, we should never judge a fine Chinese coffee from Pu’er in the same manner as a fine coffee from Sumatra, Indonesia. While some aspects will correlate, many will be entirely different. Likewise to judge a Panama Geisha on the same scale as a Kenyan coffee using only one metric is foolish.

If you want to buy a coffee to roast for other people, let’s consider the bigger picture. What are their needs and desires. How can we best serve them?